Written By: Ben Cosgrove

Even in America, where poetry is largely looked upon as an elitist indulgence rather than a cultural force to be reckoned with, Robert Frost’s works—or parts of his works—are familiar to vast numbers of people. They might not know that the words were first penned by the Bard of New England, but men and women who haven’t cracked a volume of poetry in decades still recognize Frost’s most memorable lines and, above all, his inimitable images:

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

— From “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”

He will not go behind his father’s saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, “Good fences make good neighbors.”

— From “Mending Wall”

Then there’s the famously short, sharp “Fire and Ice,” first published in December 1920:

Some say the world will end in fire,

Some say in ice.

From what I’ve tasted of desire

I hold with those who favor fire.

But if it had to perish twice,

I think I know enough of hate

To say that for destruction ice

Is also great

And would suffice.

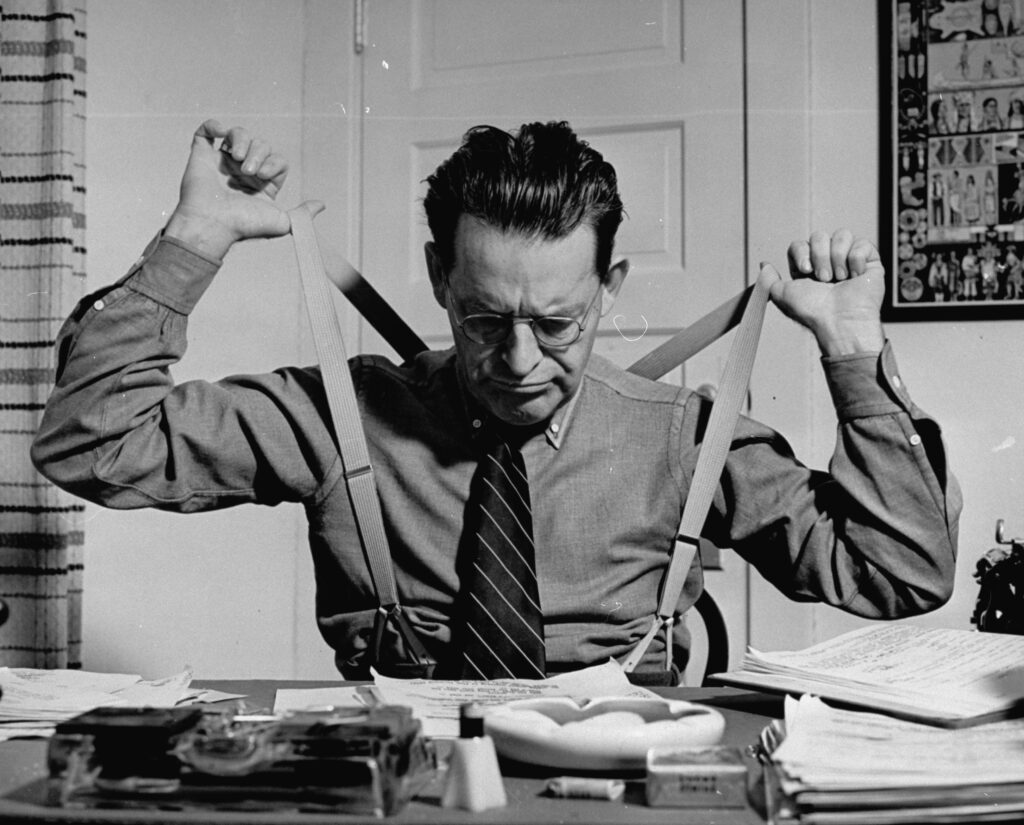

Frost won four Pulitzer Prizes for his poetry—one of a very small handful of writers to have won so many—and remains, a full half-century after his death in 1963, one of the most celebrated and popular American literary voices of the 20th century. Here, LIFE.com pays tribute to the man (b. March 26, 1874, in San Francisco) and the artist with a series of photos made by Howard Sochurek in England in 1957.

When 83-year-old Robert Frost went to England this summer [LIFE told its readers] it was officially to receive that country’s highest scholastic acclaim, honorary degrees from Oxford and Cambridge. Unofficially, it was a fine opportunity for the famous American poet to “round off his life,” as he put it, and revisit the peaceful haunts of Gloucestershire where he had lived as a younger man. In 1912, unknown as a poet in the U.S., Frost had begun a two-and-a-half-year sojourn in England and his first two books, “A Boy’s Will” and “North of Boston”, were published by an English firm. Accompanying him on his nostalgic return was LIFE’s Howard Sochurek, who caught the poet reminiscing in scenes that inspired at least eight of his later works. Back in the U.S. now, Frost regards his trip as “one of the biggest adventures of my life.”

Frost’s life was marked by enormous loss: only two of his and his wife Elinor’s six children outlived him. Elinor died in 1938. Frost himself suffered from depression, as did several other members of his family. And yet he left behind a body of work as clear-eyed and as uplifting as that of any American writer before him, or since.

In an English field where ‘Surging, the grasses dizzied me of thought’ (from ‘My Butterfly’), Frost recalled another day.

Howard Sochurek The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

“In ‘the thick old thatch, Where summer birds had been given hatch” (from ‘The Thatch’), Frost looked from the cottage in Dymock where his friend, poet Wilfrid Gibson, lived in 1914.

Howard Sochurek The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Malvern Hills, in England, where Robert Frost once lived.

Howard Sochurek The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Frost, who once wrote, ‘I never heard of a house that throve . . . where the chimney started above the stove,’ examined the stove of his old kitchen at Little Iddens, Gloucestershire

Howard Sochurek The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Malvern Hills, England, where Robert Frost once lived.

Howard Sochurek The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Nature lover Frost, who once farmed “a pasture where the boulders lie/As touching as a basket full of eggs,” stooped suddenly in this English pasture to grasp a stone and throw it.

Howard Sochurek The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Past the tree which could have been model for his line “Tree at my window, window tree . . . ,” Frost gazed sadly in the direction of the cottage, now in ruins, where he wrote it.

Howard Sochurek The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Malvern Hills, where Robert Frost once lived.

Howard Sochurek The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Robert Frost in 1957, during a visit to the English countryside where he once lived.

Howard Sochurek The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Robert Frost in an English meadow, 1957.

Howard Sochurek The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock