Ask a dozen military historians to name the single most pivotal battle or campaign of World War II the one operation that saw the war’s momentum irrevocably swing from the Axis to the Allied powers and you’ll get a dozen answers. Did the pendulum shift as early as the Battle of Britain? At Midway? During the liberation of Paris? Kursk? The Battle of the Bulge? Stalingrad? A definitive answer is impossible.

But one campaign that everyone agrees was a significant turning point in the Allied effort was launched in July 1943. Before dawn on July 10 of that year, 150,000 American and British troops along with Canadian, Free French and other Allies, and 3,000 ships, 600 tanks and 4,000 aircraft made for the southern shores of the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea: the storied, 10,000-square-mile land of Sicily. Within six weeks, the Allies had pushed Axis troops (primarily Germans) out of Sicily and were poised for the invasion of mainland Italy and one of the most arduous 20 months of the entire war: the long, often brutal Italian Campaign.

Tens of thousands of troops, on both sides, were killed or listed as missing, while hundreds of thousands more were wounded. And, of course as in most every major campaign of the war hundreds of thousands of civilians were killed, while countless more were wounded, raped, left homeless and otherwise traumatized.

Here, LIFE.com presents a series of both rare and classic color pictures made throughout the Italian Campaign by the great Carl Mydans.

Finally, it’s worth noting that, within weeks of the start of the invasion of Sicily, the Fascist dictator Benito Mussolini, who had ruled Italy for more than two decades, was booted from power and arrested. “Il Duce” subsequently escaped, with German help, and was then on the run or in hiding without cease for almost two years. He was captured by Italian partisans in late April 1945, summarily executed, and along with his mistress and several other Fascists literally hanged by his heels, in public, for all to see.

In early May 1945, the war in Europe ended.

American jeeps traveled through a bombed-out town during the drive towards Rome, World War II.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

American armor moved up the Appian Way during the drive towards Rome.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

American soldiers marched up the Appian Way during the drive towards Rome in World War II.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

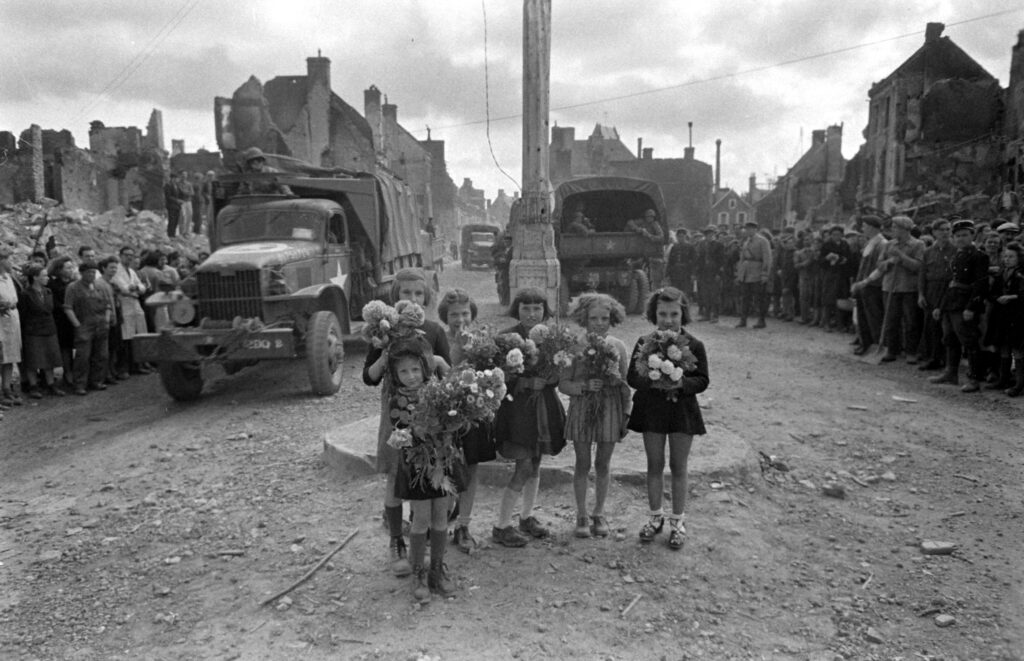

Italians watched American armor pass during the drive towards Rome along the Appian Way, World War II.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

A column of American medical vehicles during the drive towards Rome, World War II.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

American soldiers rested in a courtyard during the drive towards Rome, World War II.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

American troops stood in front of a bombed-out building during the drive towards Rome, WWII.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Ruins of the town of Monte Cassino, a result of massive Allied bombing during an attempt to dislodge German troops occupying the city, 1944.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Ruins in the Rapido Valley, 1944.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

A German graveyard along the Esperia Road, photographed during the Allied drive towards Rome, World War II.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Troops in the Liri Valley, on the road to Rome, Italian Campaign, 1944.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

An American soldier tried to spot German positions during the Allied drive towards Rome, 1944.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Liri Valley, on the road to Rome, 1944.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

American troops camped by the roadside during the drive towards Rome, 1944.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

An American soldier slept on a pile of rocks during the drive towards Rome, 1944.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Liri Valley, on the road to Rome, 1944.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

In the Rapido Valley, 1944.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

American troops rested in a field during the drive towards Rome, 1944.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

An American soldier took a meal break during the drive towards Rome, 1944.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

American troops looked over German armor destroyed during the drive towards Rome, 1944.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

The Italian Campaign, World War II, 1944.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

British and South African soldiers held up a Nazi trophy flag while combat engineers on bulldozers cleared a path through the debris of a bombed-out city, Italian Campaign, World War II.

Carl Mydans/Life Pictures/Shutterstock