You might say Helena Rubinstein’s story began at 16, when her father renounced her for refusing an arranged marriage in the Jewish district of Krakow where she grew up. You might say it began when she ventured to Australia and, bombarded with questions from sunburned ladies about how she maintained her fair complexion, smelled a profit.

Whichever origin story you favor, it’s safe to say that where the story ends multimillionaire magnate of a four-continent cosmetics empire that redefined beauty for generations of women may surprise those whose memory goes only as far back as Sheryl Sandberg and Marissa Mayer.

Today there are more female CEOs than ever, but the number of offices they fill in the C-suite remains few. In Rubinstein’s time she established her business in 1903, opened her first New York salon in 1915 and amassed $25 million by the time LIFE profiled her in 1941 they were as rare as a sunburn on Madame’s face.

An exhibit at the Jewish Museum in New York City, “Helena Rubinstein: Beauty Is Power,” is the first to explore the influence and artifacts of Rubinstein’s life. (The exhibit, which ends on March 22, will travel to the Boca Raton Museum of Art, where it will be on view beginning on April 21). Rubinstein’s legacy is less about the fact that her brand existed than it is about the message it conveyed, says Jewish Museum curator Mason Klein. Her flavor of beauty for the masses “served not only to level the snobbish aesthetic taste that was upheld by others” like her longtime rival Elizabeth Arden “but, more importantly, to expand the notion of who and what could be considered beautiful.”

It might raise some eyebrows to suggest that the mass marketing of skin creams and mascara would positively influence women’s feelings of self-worth. But Rubinstein’s mission was not just to change how women look. It was to give women the ability to define their interior lives too. “She didn’t really want her clientele to think of going to a salon and being made over like you paper a room or reupholster a piece of furniture,” Klein says.

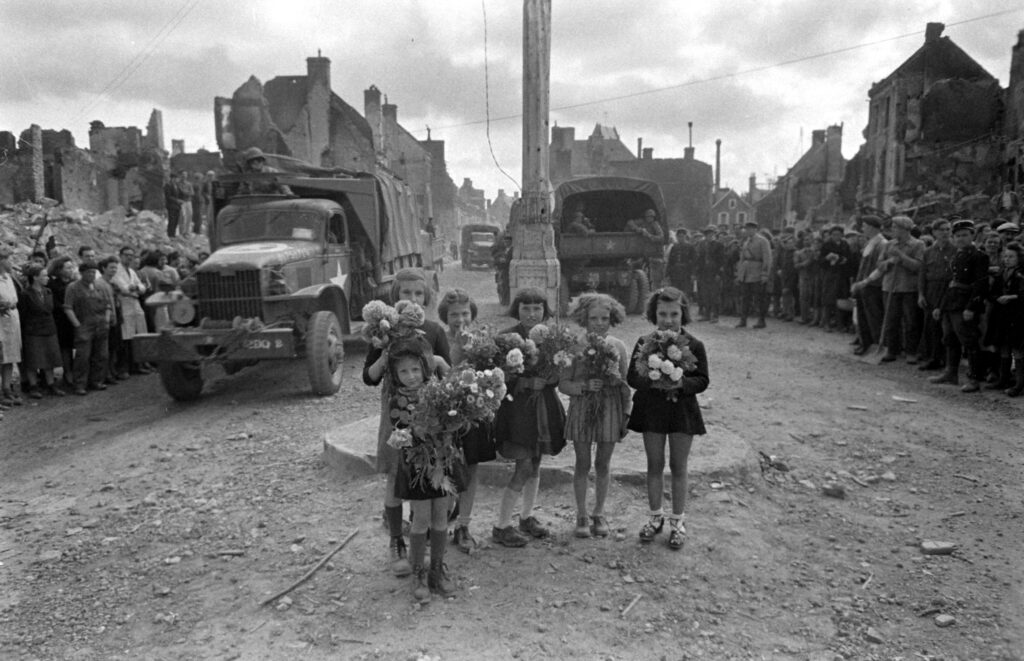

During a day at the Rubinstein salon (which could be found in more than a dozen cities worldwide), a woman could expect to be “stretched, exercised, rubbed, scrubbed, wrapped in hot blankets, bathed in infra-red rays, massaged dry and massaged under water, and bathed in milk all before lunch.”

But when the milk baths were over, the salon Rubinstein conceived of shared more than a name with the literary salons she frequented in Paris. With the fortune she amassed, Rubinstein had become both a patron of the arts and a discerning collector, boasting one of the first extensive collections of Latin American art and one of the most important early collections of African and Oceanic art. For her, there was no line between commercial beauty and modern art and if there was, she was trying to blur it.

A patron of Helena Rubinstein’s salons which operated at a loss but helped evangelize her line of 629 products learned about art, design and color, developed her own personal taste and incorporated it into the way she presented herself to the world. According to Klein, with “her encouragement of women to trust their own instincts and her advocacy of exceptionality at a time when non-conformism was taboo, she offered women this ideal of self-invention, and that’s a fundamental principle of modernity.”

Getting to international magnate status requires an ingredient many women are told is unbecoming: self-promotion. LIFE wrote that despite Rubinstein’s genius for marketing she was, among other things, an early adopter of the white lab coat uniform “Rubinstein’s greatest promotion … is undoubtedly herself.” She commissioned portraits by artists from Warhol to Picasso, and featured prominently in her own ads. A couple of inches shy of five feet tall, before an important meeting she often placed a cushion under her seat to increase her stature, letting her legs dangle behind her desk.

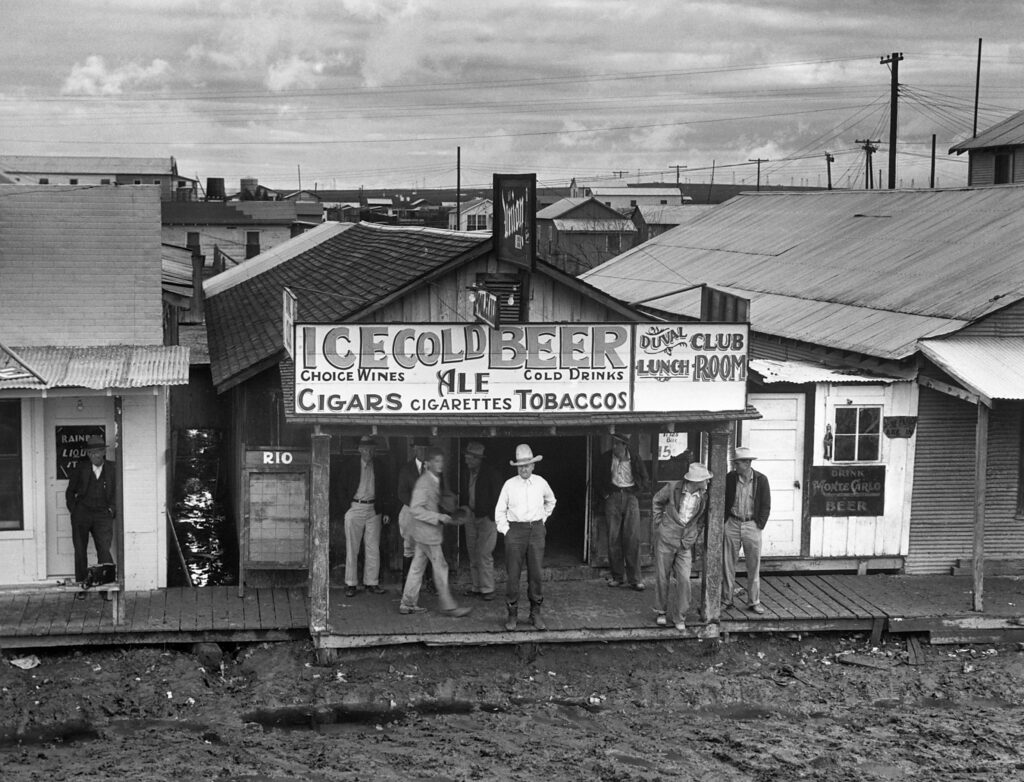

Success on this level also requires a shrewd business savvy, and Rubenstein was nothing if not conservative with the company coffers. “If somebody offered Rubinstein a package of gum for a nickel she would say “too much,”” one associate told LIFE, “in the hope that it was the only package of gum in the world that could be bought for four cents.” And she sniffed out new markets with the same discerning nose she used to nix or approve perfume scents. “Ever on the lookout for new sales openings,” LIFE wrote in 1941, “she has lately been turning over in her mind the idea that perhaps the beauty business has exploited only half its potential market.” As she put it herself: “Men could be a lot more beautiful.”

Rubinstein made a bold decision, too, in keeping her name at a time when anti-Semitism kept her flagship storefront relegated to 5th Avenue side streets for two decades. (Money, of course, was a powerful tool in the face of discrimination. When she tried to upgrade from one posh Park Avenue apartment to another with a bigger balcony, she was told that the owner didn’t rent to Jews. She promptly told her accountant to buy the whole building.) Emblazoning her name on products and advertisements not only affirmed her identity (even as a non-practicing Jew), but appealed to the masses of immigrant women pouring into the country, going to work and seeking to define their identities in America.

When Helena Rubinstein equated beauty with power, her aim was not only profit, but empowerment. Reflecting on her life in 1964 at an age she called “older than you think,” she told LIFE she squeezed 300 years of work into a single lifetime. “Shrugging like a Jewish grandmother she claims, “I did it not for money but because I love work. I will never retire.””

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter at @LizabethRonk.

Helena Rubinstein, 1941

Herbert Gehr The LIFE Images Collection/Shutterstock

Helena Rubinstein, 1941

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Helena Rubinstein, 1941

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Helena Rubinstein Salon, 1937.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Helena Rubinstein Salon, 1937.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Helena Rubinstein Salon, 1937.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Helena Rubinstein Salon, 1937.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Helena Rubinstein Salon, 1937.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Helena Rubinstein, 1941

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Helena Rubinstein, 1941

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Helena Rubinstein, 1941

Herbert Gehr The LIFE Images Collection/Shutterstock

Helena Rubinstein products, 1941

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock