If you were to observe a group of children playing war today, you might see them launching make-believe drones and deactivating imaginary IEDs. If you watched the same activity in 1968, you might have seen them parachuting out of cardboard-box helicopters or tossing plastic grenades. But in 1959, kids playing war were pint-sized guerrillas wearing flat-brimmed army hats and Castro beards made of dog fur.

In the spring of 1959, Fidel Castro was settling into his new role as Prime Minister of Cuba. Castro and his 26th of July Movement the revolutionary army named for the 1953 attack that began the Cuban Revolution had overthrown U.S.-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista and were now looking to implement a socialist agenda for Cuba. Meanwhile, in the U.S., a toy manufacturer was capitalizing on the news with a brand new product, as LIFE explained:

The hairy specter which once haunted Fulgencio Batista in Cuba is rising again incongruously to startle parents in the U.S. The latest novelty for moppets is a battle cap with fur chin strap which will turn any youngster, male or female, into a miniature version of Fidel Castro’s Cuban rebels.

Looking back on those days with the benefit of hindsight, the photographs of carefree youngsters take on a more sinister tint. To those who regard Castro as a totalitarian strongman with no concern for human rights, these images are disturbing: laughing children, ignorant of what was really going on in the world, costumed as a man who was busily tightening his control on a terrified nation. And the children may seem no less naive to those who view Castro as a hero dedicated to the fight against inequality and imperialism.

When LIFE published a selection of these photos in 1959, it was undoubtedly intended as a lighthearted story about children mimicking the serious business of adults in a complicated world. Castro was a mere two months into a half-century regime for which there were still high hopes, and the controversial policies he would implement in the ensuing decades were still unwritten history.

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

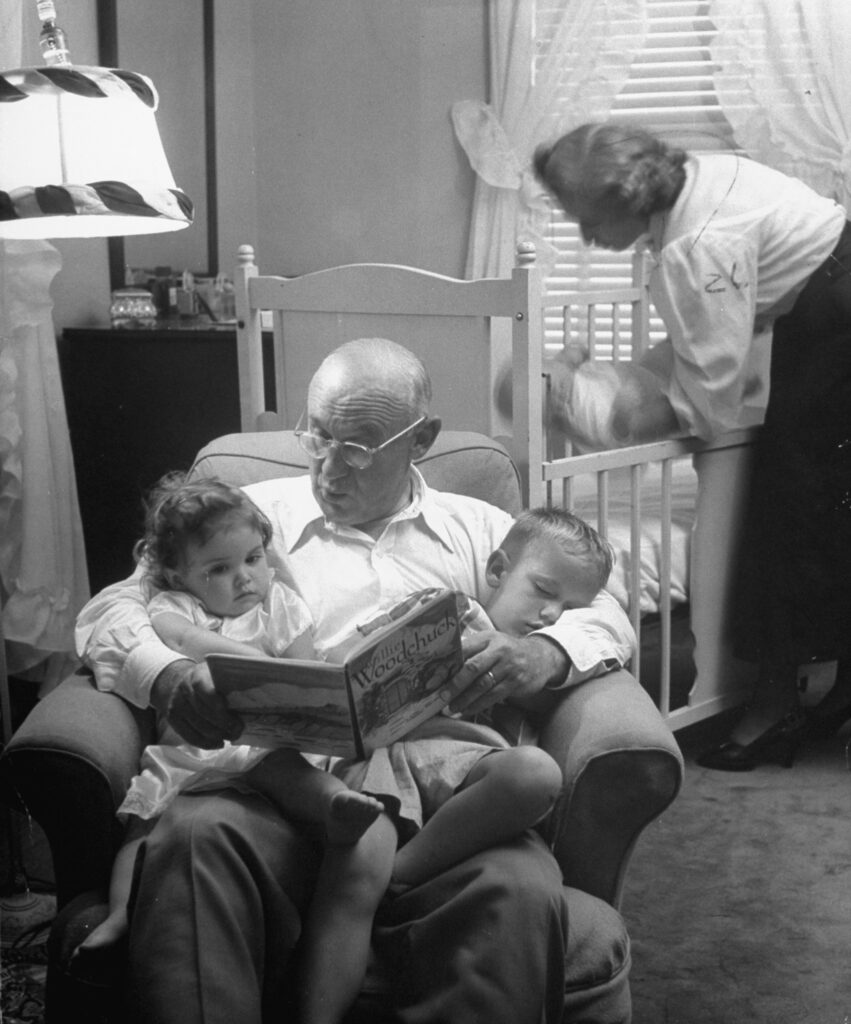

Catro-bearded babes in the woods

Ralph Morse The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Catro-bearded babes in the woods

Ralph Morse The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Catro-bearded babes in the woods

Ralph Morse The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Catro-bearded babes in the woods

Ralph Morse The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Catro-bearded babes in the woods

Ralph Morse The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Catro-bearded babes in the woods

Ralph Morse The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Catro-bearded babes in the woods

Ralph Morse The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Catro-bearded babes in the woods

Ralph Morse The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Catro-bearded babes in the woods

Ralph Morse The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Catro-bearded babes in the woods

Ralph Morse The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock