Sunglasses, as a concept, have been around for centuries—the early Inuit wore eye masks with slits cut through them to protect their eyes from the rays of the sun. But it wasn’t until the 20th century that sunglasses made the transition from protective wear to fashion accessory, even for those who were nowhere near the beach. LIFE first reported on the burgeoning trend in a 1938 story titled “Dark Glasses are New Fad for Wear on City Streets.”

Here’s how LIFE introduced the topic back then:

For years Hollywood stars have worn dark glasses to protect their eyes from the harmful glare of the kleig lights, and to conceal their identity from curious fans. Now dark glasses have become a favorite affectation of thousands of women all over the U.S.

LIFE reported that the sunglasses trend was already widespread, with an estimated 20 million pairs of shades sold in the U.S. the previous year. The story suggested this was somewhat frivolous because people with darker eyes had a natural protection against excessive light, and thus, “Of the millions who wear [sunglasses] about 25% really need them.” The photos for the story were shot by Alfred Eisenstaedt.

In 1948 LIFE was back to report on the latest innovation in the field: mirrored sunglasses. The story reported that “the new glasses can be used as handy make-up mirrors, and they can hide black or bloodshot eyes completely.” A fun photo shoot by Martha Holmes celebrated the novelty.

This gallery includes images from those two early stories, as well as some other pictures from favorite LIFE shoots over the years. While the magazine’s early coverage talked more about eye protection, over time it became clear that that having fun—see especially Stan Wayman‘s shoot on “super specs”—and looking good were at the heart of sunglasses’ appeal.

A 1938 LIFE story touted the “new fad” of wearing sunglasses in the city.

Alfred Eisenstadt/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

A 1938 LIFE story touted the “new fad” of wearing sunglasses in the city.

Alfred Eisenstadt/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

A 1938 LIFE story touted the “new fad” of wearing sunglasses in the city.

Alfred Eisenstadt/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

A 1938 LIFE story touted the “new fad” of wearing sunglasses in the city. This novelty style, known as “blinkers,’ was made of pressed celluloid and LIFE noted that they would be dangerous for drivers to wear because of poor side vision

Alfred Eisenstadt/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

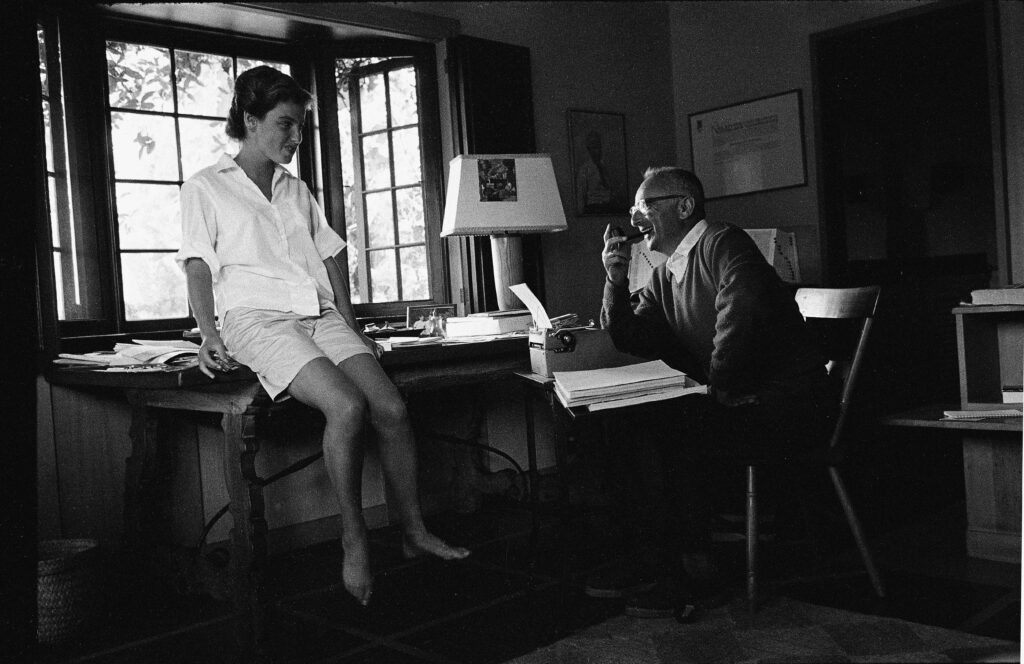

From a 1938 LIFE story touting the “new fad” of sunglasses.

Photo by Alfred Eisenstaedt / LIFE Picture Collection via Shutterstock

A teenage girl in Tulsa, Oklahoma used nail polish to decorate her sunglass frames, 1947.

Nina Leen/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

A 1948 story highlighted the new trend of mirrored sunglasses.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

A 1948 story highlighted the new trend of mirrored sunglasses.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

A 1948 story highlighted the new trend of mirrored sunglasses.

Martha Holmes/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

These silly sunglasses featuring long blue eyelashes and small lenses were dreamed up by designer Schiaparelli, and brought a lighter note to the generally conservative spring showings in Paris, 1951.

Gordon Parks/The LIFE Picture Collection © Meredith Corporation

This woman’s “I Like Ike” sunglasses honored the star of the 1956 Republican National Convention in San Francisco.

Photo by Leonard McCombe/The LIFE Picture Collection © Meredith Corporation

From a 1960 story on oversized “super specs.”

Stan Wayman/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

From a 1960 story on oversized “super specs.”

Stan Wayman/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

From a 1960 story on oversized “super specs.”

Stan Wayman/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

From a 1963 LIFE story on sunglass fashions.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

From a 1963 LIFE story on sunglass fashions.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

From a 1963 LIFE story on sunglass fashions.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

From a 1963 LIFE story on sunglass fashions.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

From a 1963 LIFE story on sunglass fashions.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

From a 1963 LIFE story on sunglass fashions.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

From a 1963 LIFE story on sunglass fashions.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

From a 1963 LIFE story on sunglass fashions.

Yale Joel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock