In 1941 Ted Williams, 22, was the center of attention in the baseball world as he pursued a .400 batting average, which was at the time a rare feat (instead of impossible, as it has seemingly become). The Red Sox outfielder famously pursued the goal that year in a manner which affirmed not only his skill at the plate but also his character.

With Boston set to play a double-header on the final day of the season, Williams’ batting average was .3996—which, under the rules of baseball, would have been rounded up to .400 to give him the mark. Boston’s manager, Joe Cronin, offered Williams the chance to sit out and protect his average, but Williams chose to play both games of the double-header. An entirely respectable day at the plate—say, 2-for-7—could have dropped his average by crucial thousandths of a percentage point, but Williams took the risk. He played both games and had six hits in eight at bats, elevating his season average to .406—no rounding needed.

His bold decision has gained significance over time because, all these decades later, Williams is the last batter to ever hit .400. No one has done it since.

Even before that historic season was over, though, LIFE had placed Williams among baseball’s elite. In its Sept. 1, 1941 issue the magazine ran a story titled “Williams of Red Sox is Best Hitter” that attempted to explain what made this young man so special.

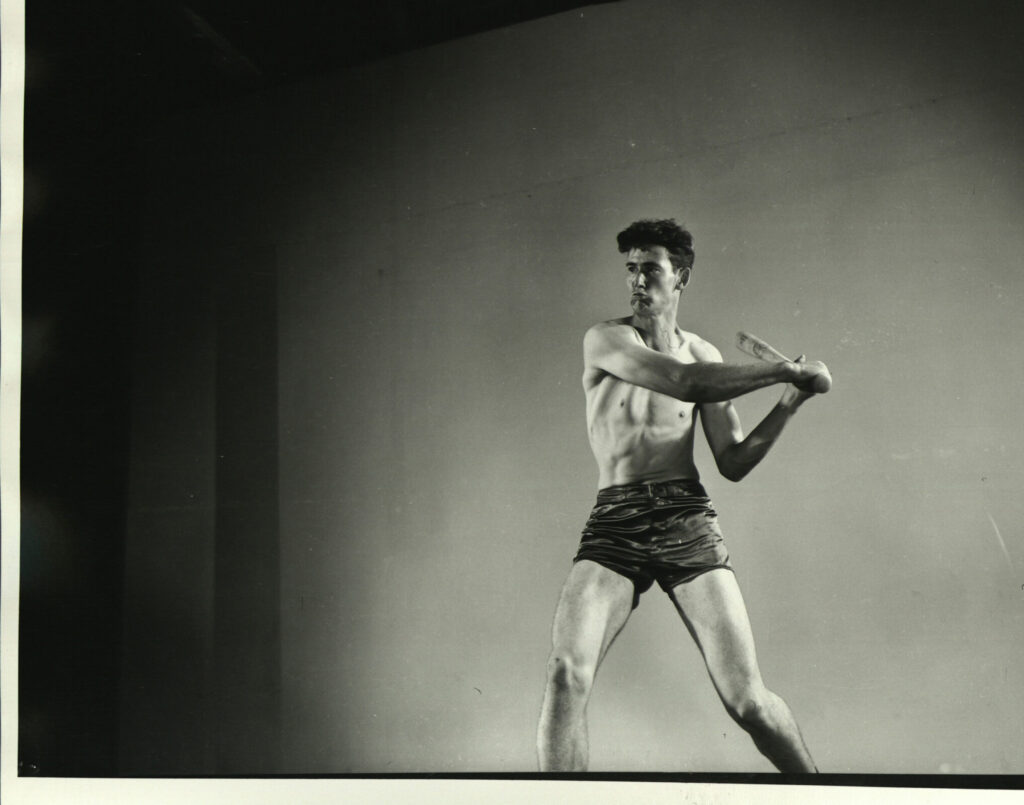

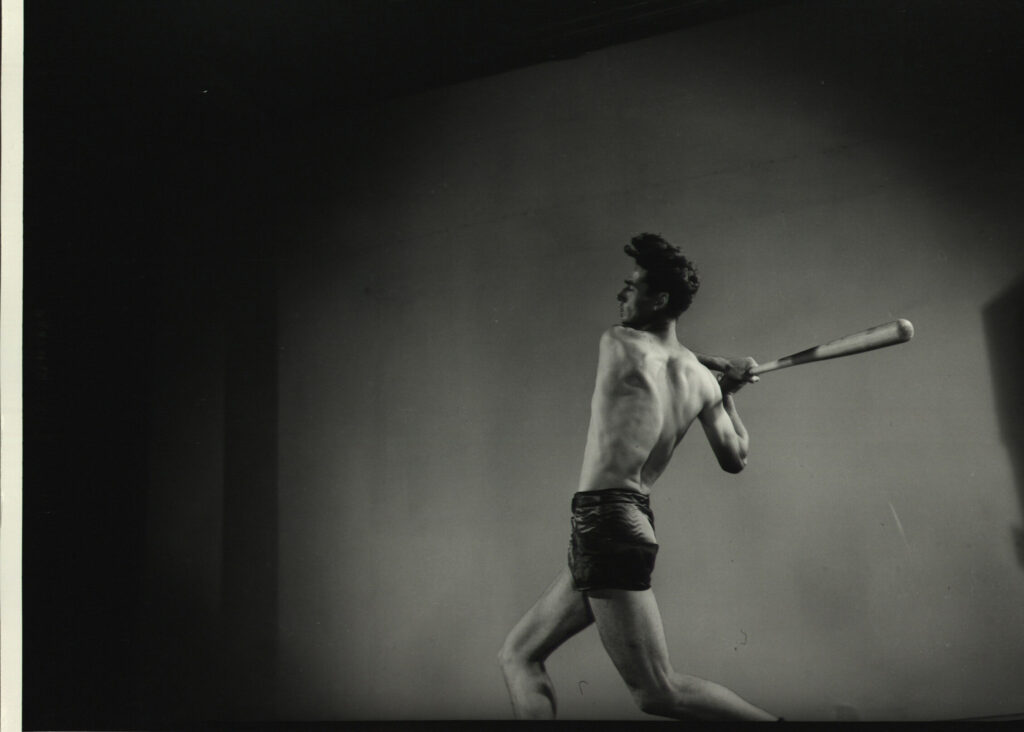

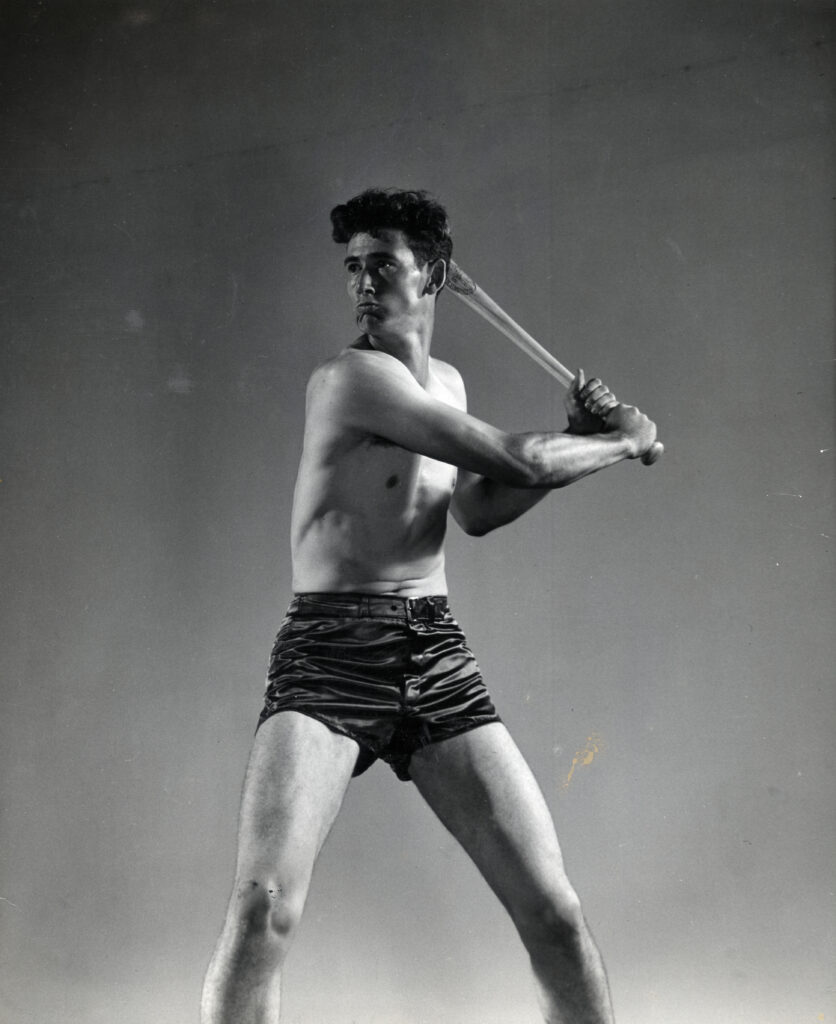

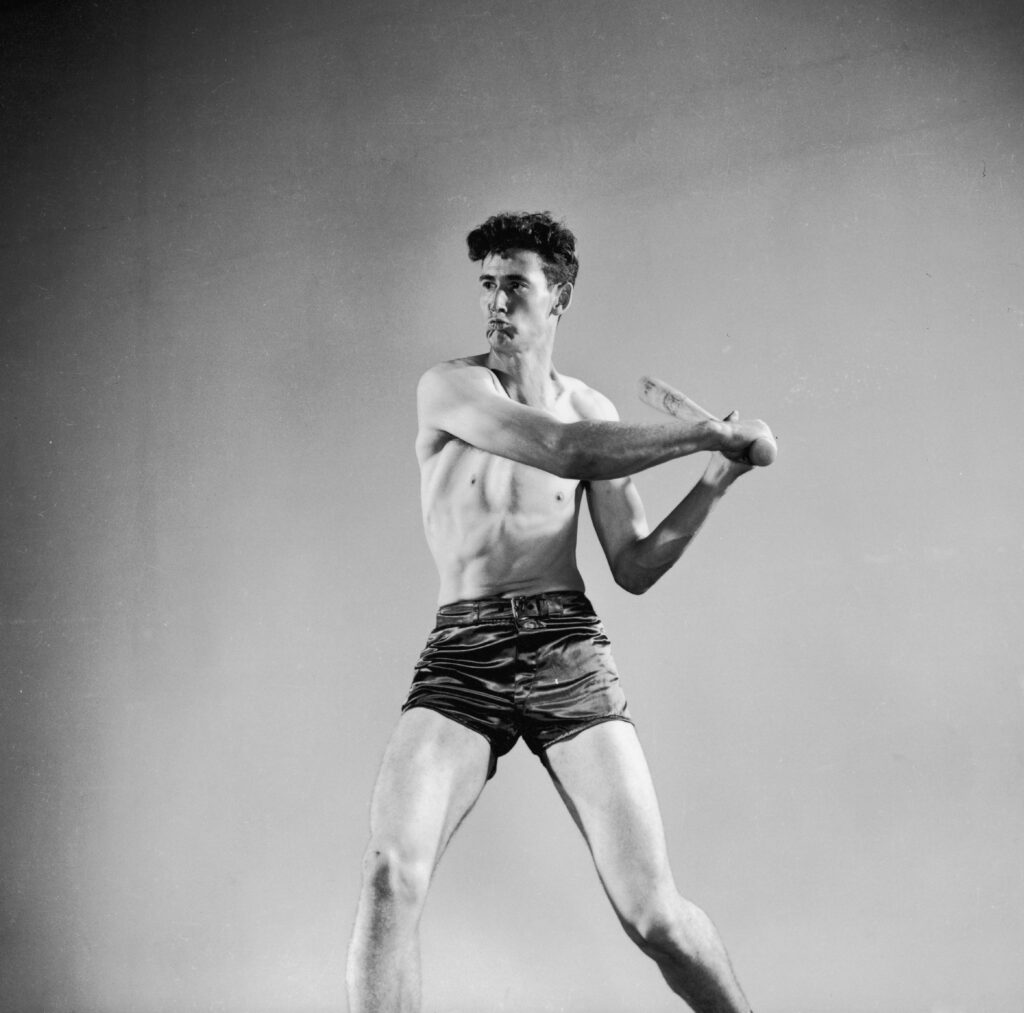

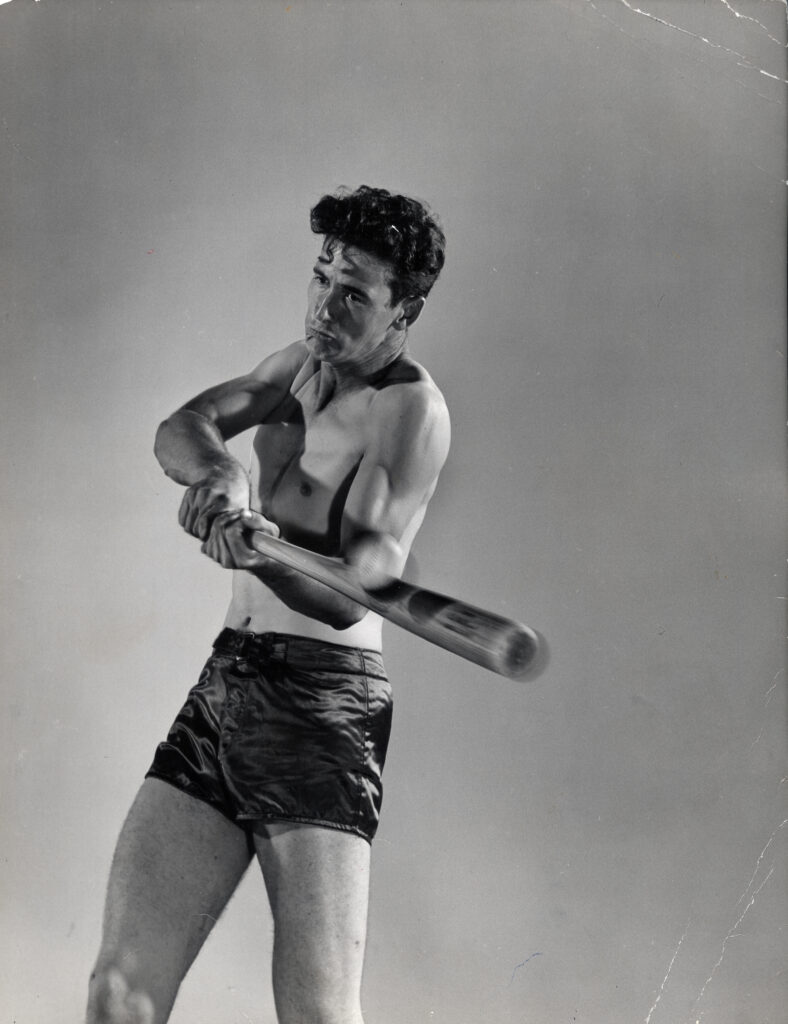

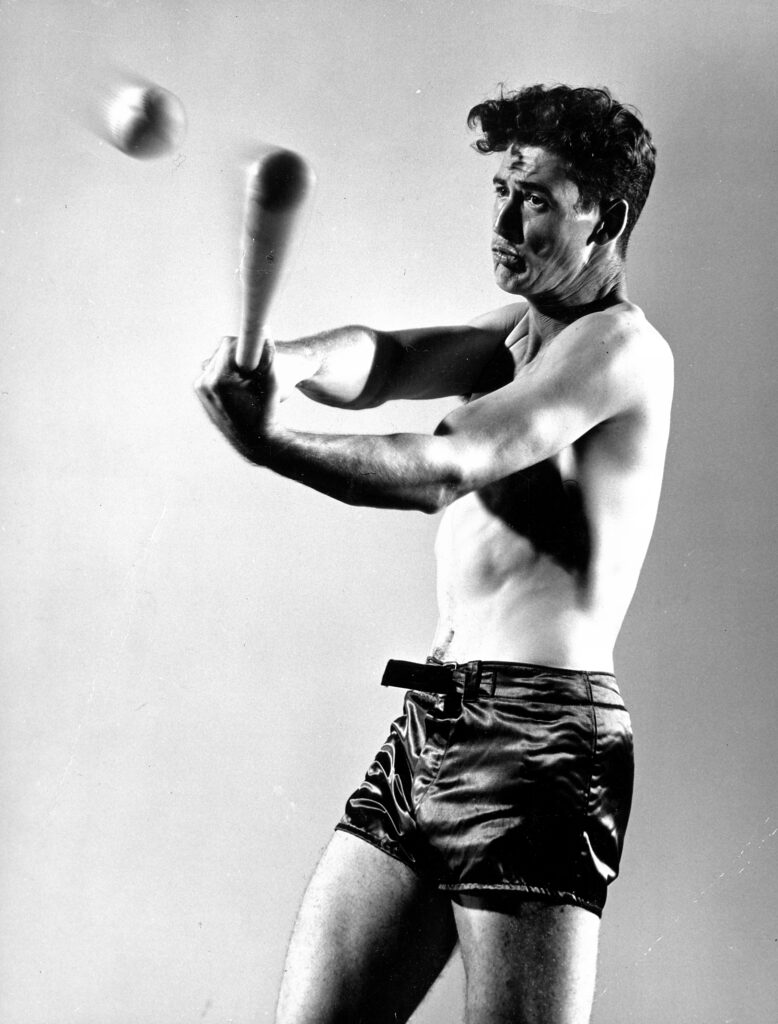

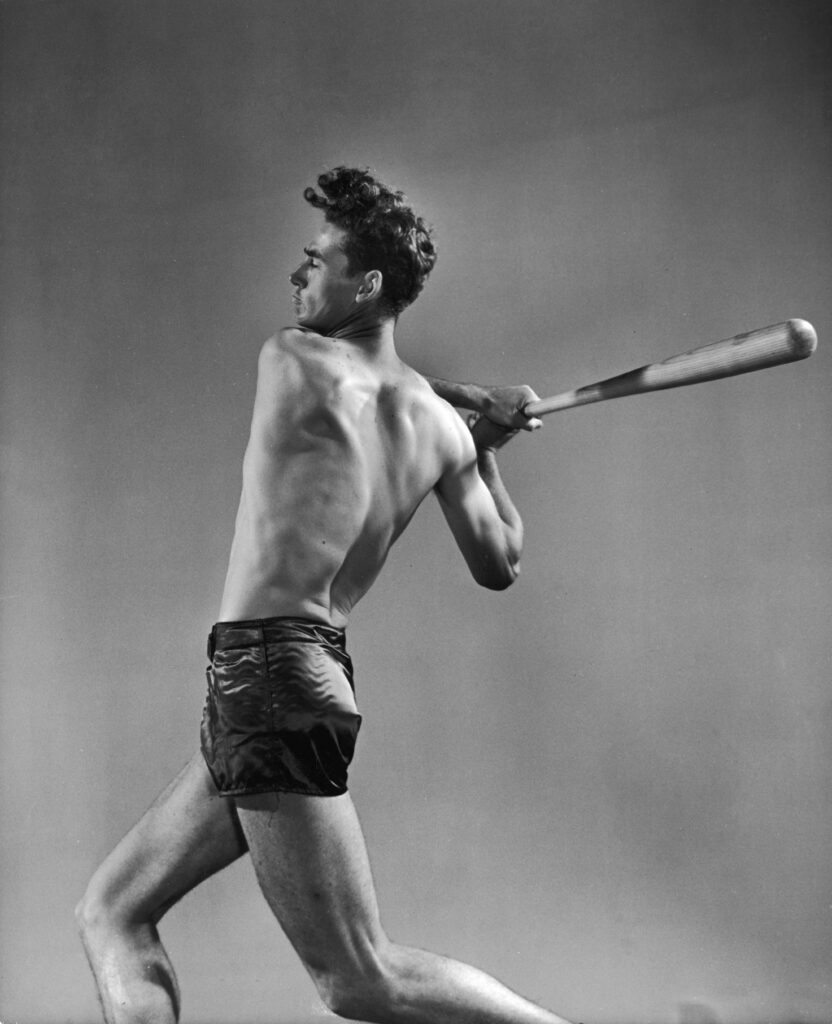

Williams is a great hitter for three reasons: eyes, wrists and forearms. He has what ballplayers call “camera eyes” which allow him to focus in on a pitched ball as it zooms down its 60-foot path from the pitcher’s hand, accurately judge its intended path across the plate, and reach for it. He even claims he can see the ball and bat meet. The rest of his formula is to never stop swinging. On and off the field he consistently wields a bat to keep the spring in his powerful wrists. Even when he is in the outfield he sometimes keeps waving his arms in a batting arc. And, more than most other great batters, he keeps his body out of his swing, puts all his drive into his forearms.

LIFE illustrated its story with studio photographs by Gjon Mili, in something of a meeting of the masters. This LIFE collection of Mili’s studio work features his stop-motion images of drummer Gene Krupa, actor/dancer Martha Kelly and artist Pablo Picasso. The inclusion of Ted Williams of their company is a telling tribute to his mastery of the art of hitting. Williams posed shirtless, which underlined that Williams relied on technique rather than muscle. The 6’3″, 175-pound Williams was skinny enough that the press nicknamed him “Toothpick Ted” and “The Boston Stringbean.”

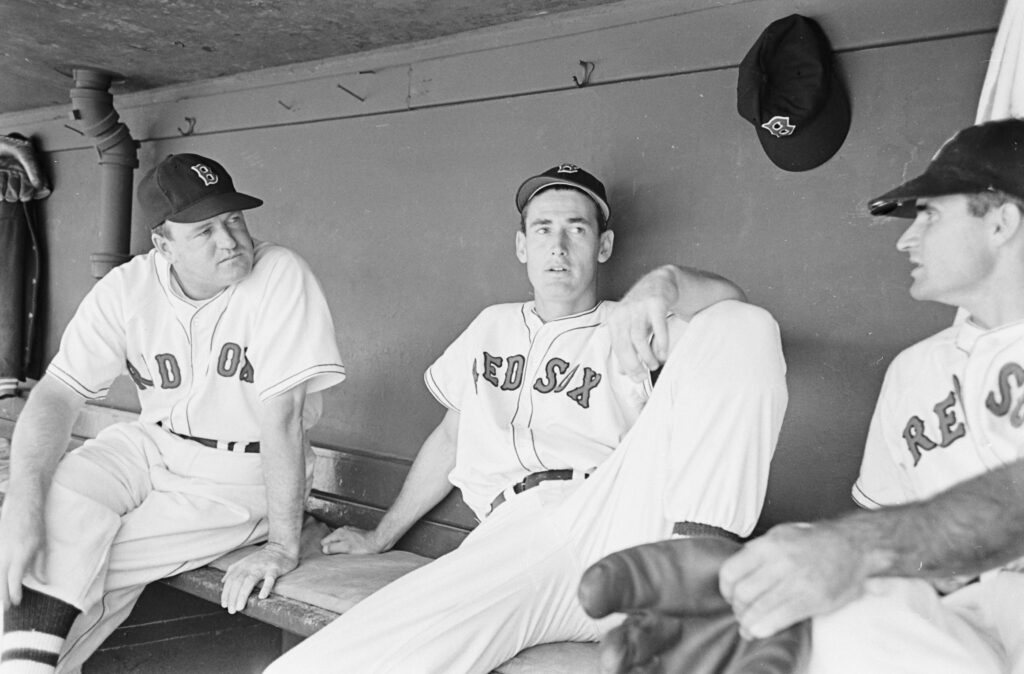

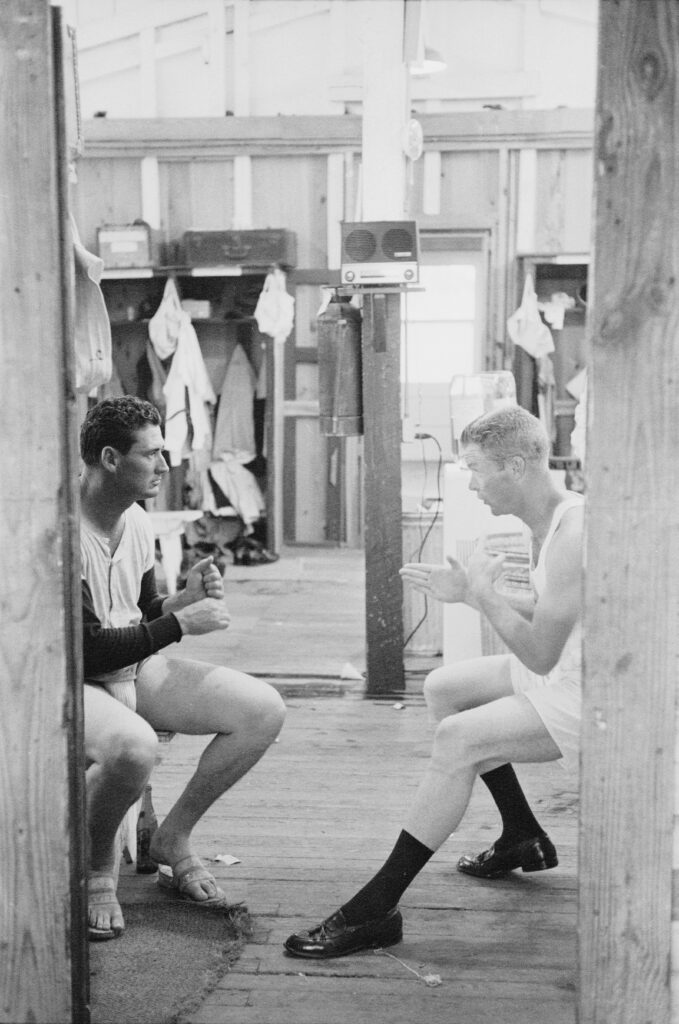

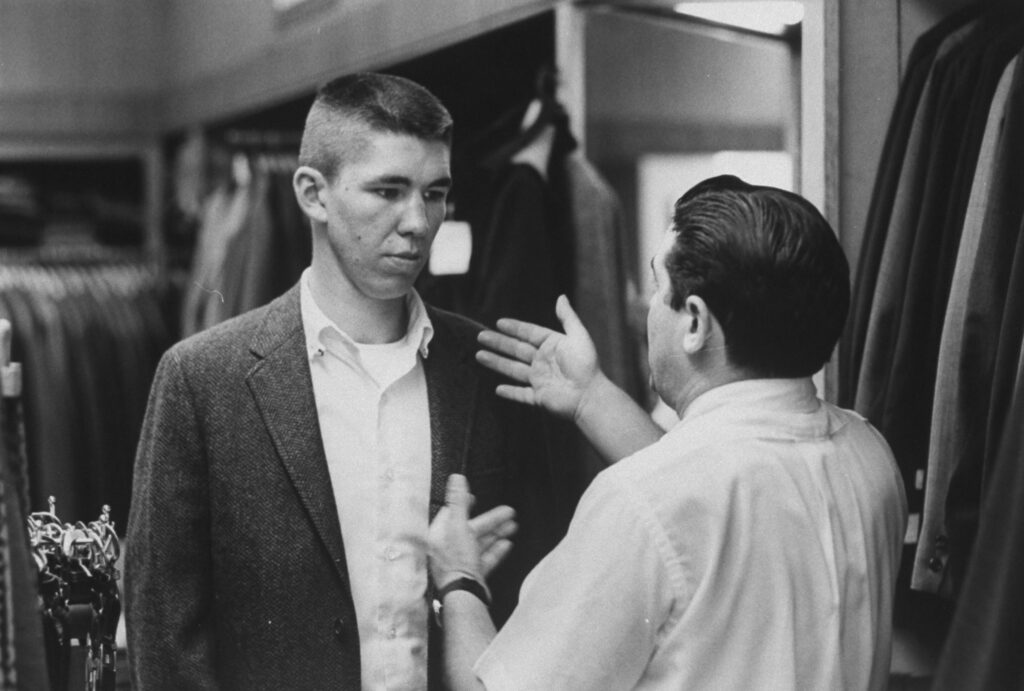

In addition to Mili’s portraits of Williams from the 1941 season, this collection includes a few other images that LIFE shot over the years of Williams in uniform. Pay special attention to the last image, taken by George Silk, which shows Williams in spring training in 1956, talking to a young player named Gordie Windhorn.

Williams was by that time a 12-time All-Star, while Windhorn was a young journeyman who was passing through Red Sox camp and would not make the roster. But Silk’s photo captures the serious and respectful way that Williams treated Windhorn, because they were talking about his favorite subject, which was hitting.

While Mili’s photos capture Williams technique and physique, that last shot hints at his obsession with his craft.

Ted Williams demonstrated his batting stroke in the studio of LIFE photographer Gjon Mili, 1947.

Gjon Mili/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Red Sox outfielder Ted Williams, 22, showed off his powerful baseball swing for photographer Gjon Mili, 1941.

Gjon Mili/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Red Sox outfielder Ted Williams, 22, showed off his powerful baseball swing for photographer Gjon Mili, 1941.

Gjon Mili/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Red Sox outfielder Ted Williams, 22, showed off his powerful baseball swing for photographer Gjon Mili, 1941.

Gjon Mili/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Red Sox outfielder Ted Williams, 22, showed off his powerful baseball swing for photographer Gjon Mili, 1941.

Gjon Mili/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Ted Williams demonstrated his batting stroke in the studio of LIFE photographer Gjon Mili, 1947.

Gjon Mili/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Red Sox outfielder Ted Williams, 22, showed off his powerful baseball swing for photographer Gjon Mili, 1941.

Gjon Mili/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

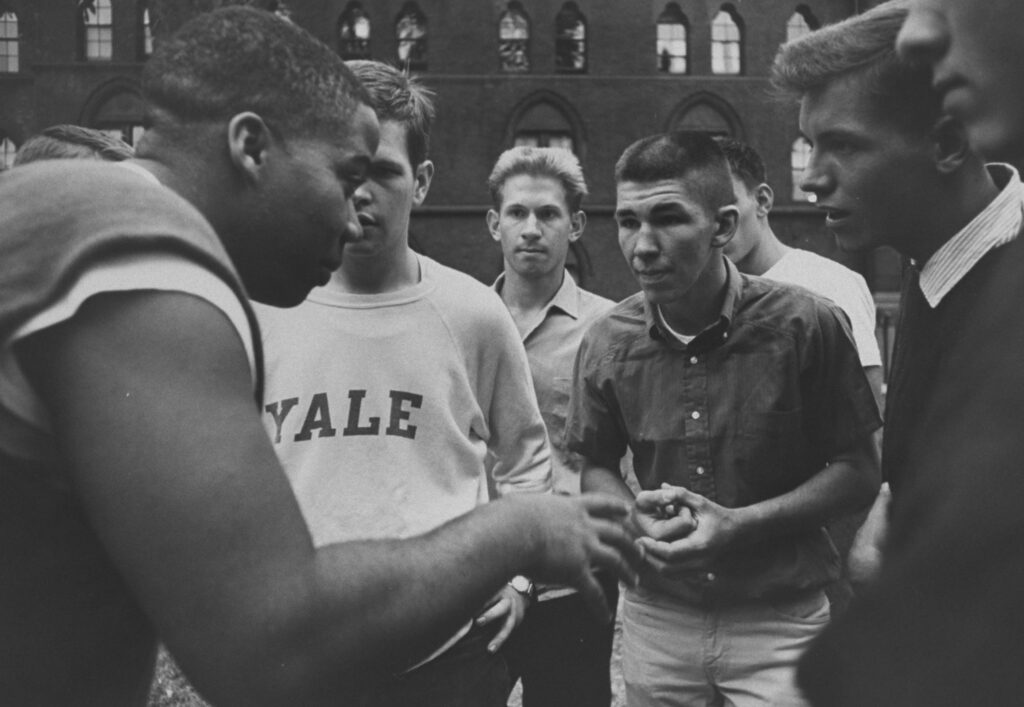

Red Sox outfielder Ted Williams, 22, demonstrated his grip on the bat for photographer Gjon Mili, 1941.

Gjon Mili/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Ted Williams sat on the bench with his Red Sox teammates, 1946.

Sam Shere/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Red Sox great Ted Williams took the field, 1946.

Sam Shere/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Ted Williams took batting practice, 1948.

Frank Scherschel/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock

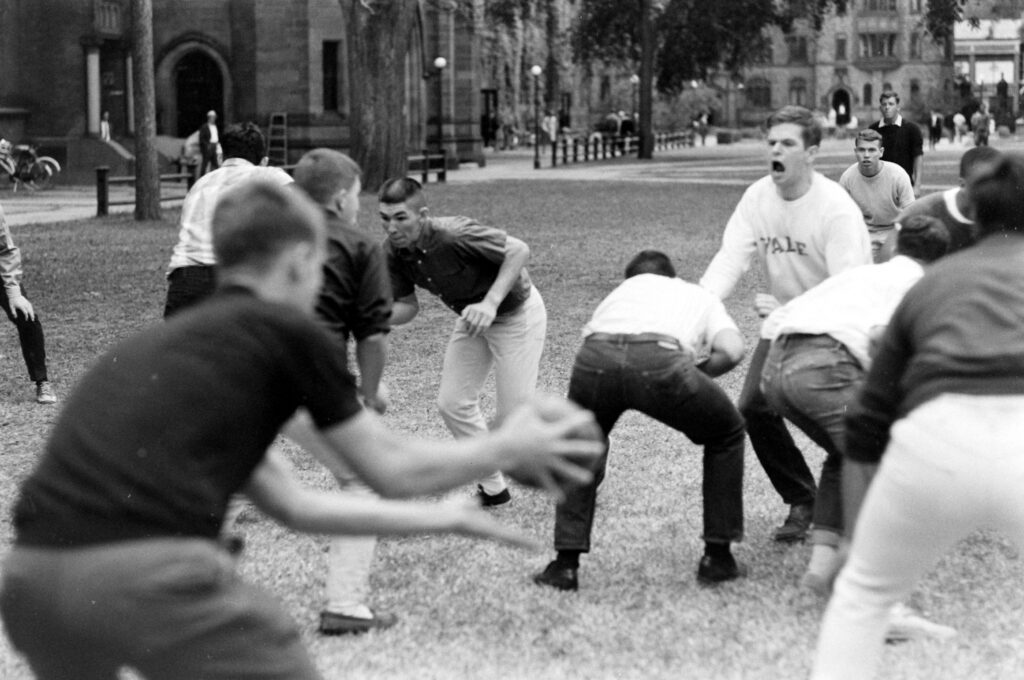

Ted Williams of the Boston Red Sox spoke with teammate Gordie Windhorn about the art of hitting during spring training in Sarasota, Fla., 1956.

George Silk/Life Picture Collection/Shutterstock