For years, one of the signature draws along the famous boardwalk in “the world’s favorite playground” of Atlantic City, N.J. was the annual Miss America pageant, long held every September in that neon city by the sea. Conceived in 1921 as a way to keep at least some of the summer crowds around and, of course, spending money after Labor Day, the pageant lit up Atlantic City for nine decades before packing up and moving, in 2006, to Vegas. (The contest returned to Atlantic City in 2013 but left again in 2019.) As the granddaddy or rather, the grandma of beauty contests, the pageant seemed to say something at once profound and quite silly about the culture that spawned it.

In fact, the reader will notice that that description might well apply to the pictures in this gallery, as well photos made by LIFE’s Alfred Eisentaedt during the 1945 competition in Atlantic City. (Only one of the pictures here, the first slide, ever ran in the magazine; the rest remained unpublished.)

Sure, there were speeches and displays of genuine talent on stage. But more often than not, the images that emerged from the two-day (now three-day) affair featured scores of women, most of whom seemed and who still seem to be cut from very much the same physical mold, wearing very small bathing suits and posing or parading in high heels.

That the Miss America title for many decades really meant Miss Caucasian America certainly undercut the pageant’s unspoken but strongly implied claim to celebrate and judge an entire nation’s loveliest and most talented women. Black women did not even begin competing in the pageant until the 1970s, and the first African-American Miss America, the wonderful Vanessa Williams, would not be crowned until 1984, a full six decades after the pageant began.

But that sort of problematic history aside, the Miss America pageant remains a signature cultural happening, while the Miss America Organization provides tens of millions of scholarship dollars annually to thousands of young women who, without that money, might not be able to attend college. In fact, it just so happens that the Miss America featured in this gallery, Bess Myerson incidentally, the first Jewish winner of the pageant was the very first Miss America to receive a scholarship as part of her victory prize.

The winner of the 1945 Miss America pageant, 21-year-old Bess Myerson of New York.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Spectators line up during the Miss America pageant festivities in Atlantic City, 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Bess Myerson, Miss America, 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Scene outside the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Scene during the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

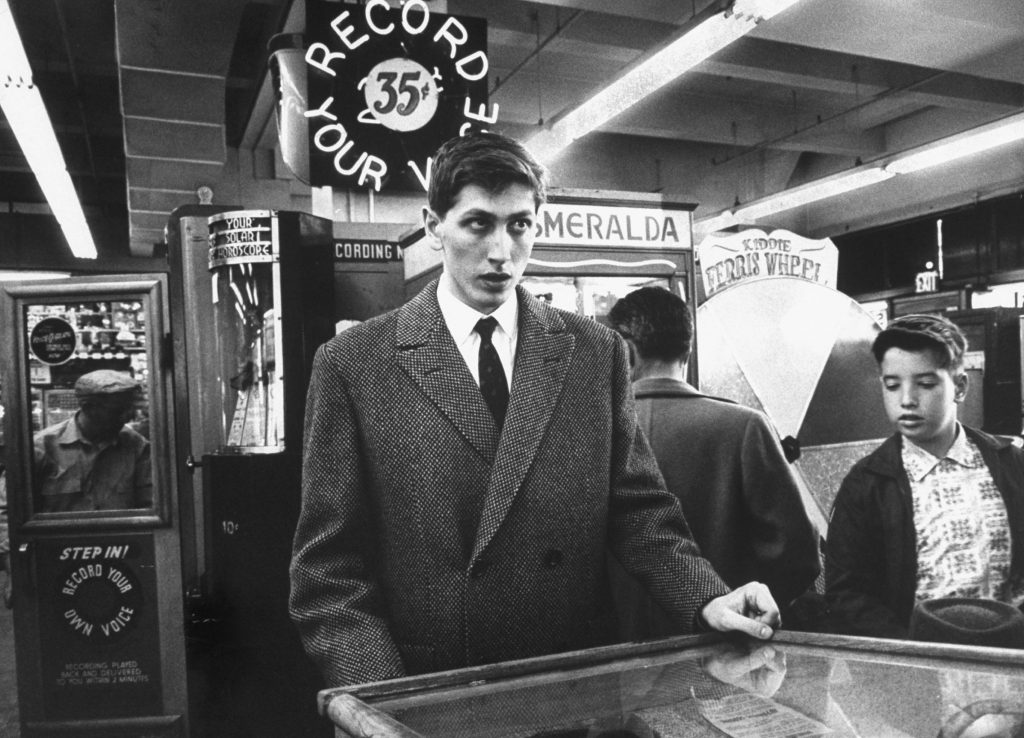

Outside the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Contestants in the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Contestant in the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Contestants in the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, September 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Inside the Warner Theater during the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, September 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, September 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, September 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Contestants in the Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, September 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Bess Myerson, Miss America in 1945, Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Bess Myerson, Miss America in 1945, meets the press, Atlantic City, New Jersey.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Miss America contestants in Atlantic City, September 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Miss America pageant in Atlantic City, September 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock

Miss America Bess Myerson (right) and friend, Atlantic City, New Jersey, September 1945.

Alfred Eisenstaedt The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock