Sports fans are notoriously contrary, but all would have to agree that “the Super Bowl” is a far better name for pro football’s ultimate contest than “the AFL-NFL World Championship Game,” which is exactly what it was called for the first two years it was played, in 1967 and 1968.

A sign that this championship wasn’t the big deal then that it is today: the game did not sell out the Los Angeles Coliseum. It is the only Super Bowl not to fill all its seats. The matchup was not expected to be competitive, and it wasn’t, especially. Vince Lombardi’s Green Bay Packers handily beat the Kansas City Chiefs 35-10, with quarterback Bart Starr being named the game’s Most Valuable Player. Starr would earn that honor again in Super Bowl II, his Packers beat the Raiders, 33-14 in Miami.

In fact, the real historical importance of these first two lopsided games between the NFL and AFL champs is that it helps explain why what happened in Super Bowl III was such a big deal. After those first two blowouts of the AFL teams, it was a true shocker when Joe Namath and his New York Jets scored that first win for the AFL, and helped pave the road to the NFL-AFL merger.

Here, LIFE.com presents a series of photos, none of which ran in LIFE magazine, made by Bill Ray and Art Rickerby before, during and after that inaugural game.

Almost everything about the Super Bowl has changed drastically in the long years since Green Bay and Kansas City took the field. That’s part of the appeal of the photos. They’re like baby pictures of a game that is about to grow up—way, way up.

The Kansas City Chiefs waited to take the field against the Packers prior to the start of Super Bowl I, Los Angeles, 1967.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Kansas City’s Fletcher Smith, with the Green Bay Packers massed behind him, prior to the start of Super Bowl I, Los Angeles, 1967.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Green Bay offensive lineman Jerry Kramer in Super Bowl I, 1967.

Art Rickerby/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Super Bowl I, 1967.

Art RickerbyLife Pictures/Shutterstock

Green Bay’s Elijah Pitts eluded Kansas City defenders, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Art Ricker/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Chiefs linebacker E. J. Holub, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Packers head coach Vince Lombardi, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Green Bay wide receiver Max McGee, Super Bowl I, 1967, was the game’s surprise star, with seven receptions for 138 yards and two touchdowns.

Art Rickerby/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Football’s escalation in the American consciousness took a great leap forward in 1967, when Bart Starr led the Green Bay Packers to a win over the Kansas City Chiefs at the Los Angeles Coliseum in the first Super Bowl.

Photo by Art Rickerby/The LIFE Picture Collection © Meredith Corporation

Super Bowl I, 1967.

Art Rickerby/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Elijah Pitts (No. 22) ran the Packers’ signature play, the power sweep, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Art Rickerby/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Tight end Reggie Carolan in the Chiefs’ locker room, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Kansas City defensive lineman Jerry Mays prior to Super Bowl I, 1967.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

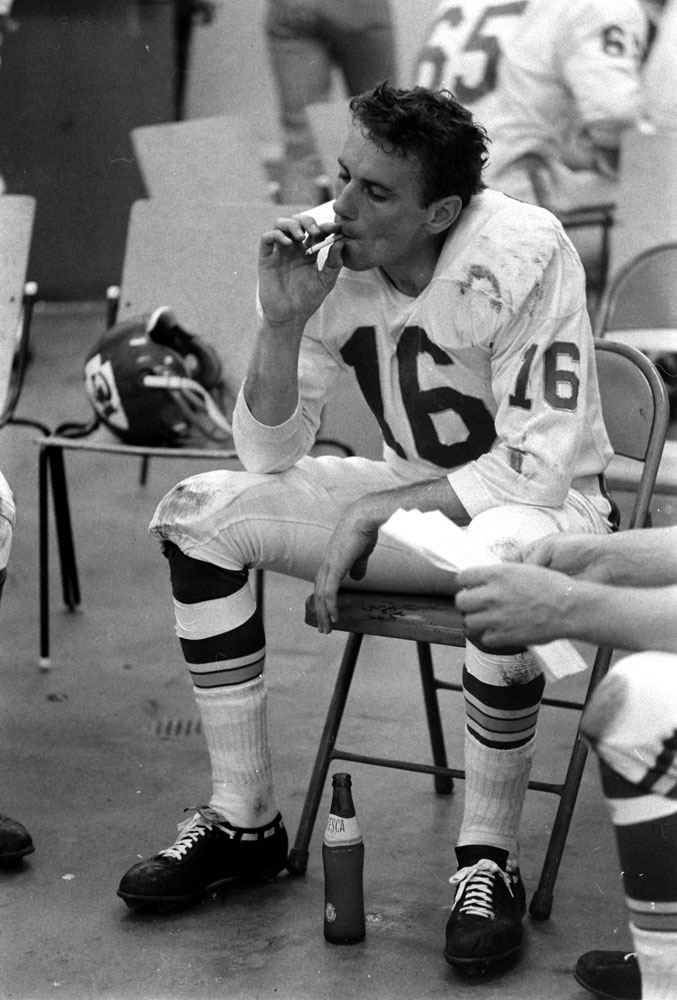

Quarterback Len Dawson in the Chiefs’ locker room, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Kansas City sideline, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Green Bay receiver Carroll Dale was hit by the Chiefs’ Willie Mitchell, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Art Rickerby/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Green Bay running back Jim Taylor (No. 31), Super Bowl I, 1967.

Art Rickerby/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Kansas City’s Fred Williamson was carried off the field after breaking his arm, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Kansas City head coach Hank Stram, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Paul Hornung (No. 5), a future Hall of Famer, did not play in the game due to injury, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Art Rickerby/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jim Taylor was tackled by the Chiefs’ Sherrill Headrick, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Art Rickerby/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jim Taylor (No. 31) in Super Bowl I.

Art Rickerby/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jim Taylor, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Art Rickerby—Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

On the Kansas City sideline, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Fred Williamson was led from the field at the end of the first Super Bowl, 1967. Williamson broke his arm during the game.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Jerry Mays and other Kansas City Chiefs, Super Bowl I, 1967.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock

The Packers’ Herb Adderley and Kansas City’s tight end Fred Arbanas headed to the lockers after Green Bay’s 35-10 victory in Super Bowl I, Los Angeles, 1967.

Bill Ray/Life Pictures/Shutterstock