Written By: Daniel D'Addario

The following is excerpted from LIFE’s new special issue celebrating the 50th anniversary of Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory, available here online and at newsstands.

Before we ever see Gene Wilder in Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory, we hear about his character’s legend.

The reclusive candymaker Willy Wonka—a figure shrouded in mystery, whose immense wealth shields him from members of the public to whom he hasn’t granted a “golden ticket”—looms large in the imagination of each character in the film. There’s no telling what he might be like, and the characters, awaiting a rare Wonka appearance, are eager to find out. His entrance is all the more uncomfortable, then, as he slowly and grimly limps out of his factory. He seems pained, grievously unhappy. The scene stretches on as we see him dragging his right leg, slowly moving toward his fans, until, in a dreadful development, he falls forward—and at the last moment breaks into a brilliantly athletic forward roll.

Wilder knew how to make an entrance, both on-screen and in the lives of fans too young to have seen The Producers. Their first glimpse of the actor, an impression that would last through the movie and throughout his career, showed he was incredibly serious about being funny, a performer who reached the laugh only by pushing through intense discomfort. Any comic can do a funny walk. Wilder found humor through catharsis. It was a somewhat mean-spirited trick, but the light of Wonka’s soul shone brighter for the dark impulses that sometimes occluded it.

The Roald Dahl novel on which the movie is based is Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, but the retitling of the movie, which was first released 50 years ago this summer, was the smart thing to do, especially in light of Wilder’s performance. The eyes gravitate to Wonka every moment he’s on-screen. There is something malevolent about this man. His smile comes rarely, and, Cheshire Cat–like, it seems to be informed by something other than pure joy.

He also takes an unusual amount of pleasure in tricking, disciplining, and tormenting his young fans. The familiar story of Willy Wonka shouldn’t work on-screen, so oddly sadistic are its undertones: Of the five children who find one of Wonka’s golden tickets for a tour of the factory, four do not complete the trip. Whatever actor plays Wonka has to be not just calm but the engineer of the mayhem. Seeing justice served for causing disorder must be more important than keeping his visitors safe. Wonka is a madman, and that we can’t stop watching him is proof of just how well Wilder could hold the screen.

Wonka’s particular mania is visible from the tour’s start. His song “Pure Imagination,” performed as he leads his charges through his personal Neverland, is punctuated with sharp shuffle steps backward and whips of his walking stick as he attempts to stop them from taking a step ahead of him. When he eventually allows them to run free, they take the opportunity to sample all his wares, and he’s left alone, singing to himself. The song downshifts to a dirge, as Wilder’s face collapses slightly. “There is no life I know to compare with pure imagination,” Wilder sings, drinking, ever more deeply from a teacup made of a flower. “Living there, you’ll be free, if you truly wish to be.”

It’s a moment fraught with double meaning. Wilder’s Wonka is many things, but he’s far from free. In fact, as we see throughout the film, his seeming liberty to create absolutely anything he might desire (contrary to physics or good sense) has kept him imprisoned. If anything is possible, nothing brings joy. Each new magnificent or strange invention we see is, to him, old hat. The only thing that Wonka is able to focus on is his obsessive insistence on rule-following. He may want to be free, but his genius binds him to a need for order. As a way to build a world in which he would be comfortable, Wonka has shut out the possibility for serendipity or real joy. It’s quite a sophisticated message for children!

The film’s didactic lessons about avoiding greed, narrated by the Oompa-Loompas, go down easier. Wilder finds in Wonka something more complex than an impresario in top hat and purple vest. As with his best work in films intended for adults, he’s conducting a high-wire act, paradoxically allowing the character’s bone-deep desire for order to give rise to madness, and finding comedy in between.

Consider a scene near the film’s end, when Wonka lashes out at Charlie, the last child left standing. Charlie has done admirably, showing that he’s nowhere near as greedy as the other tour-goers. Yet he did sample a drink he wasn’t supposed to during the tour. Wonka, who simply sat by bemused when, say, poor Violet Beauregarde blew up into a blueberry, is outraged, raising his voice in a way he hasn’t before. “You lose!” he says to Charlie and the boy’s elderly grandfather, practically vibrating with rage, betrayed and broken. “Good day, sir!” This, too, is a test. By returning a magical candy he has received rather than giving it to one of Wonka’s rivals, Charlie proves his honesty. The entire exchange exists somewhere between reality—we believe Wonka is angry about the theft—and elaborate ruse. The genius of Wilder’s portrayal is that both exist at once, and the film’s finale allows Wonka to repeat the trick he played at the film’s beginning. Once more, he turns a display of pathos into a soaring trick, taking Charlie up in his “Wonkavator” to survey the entire town, his face breaking into a devious grin. For Wilder in this role, the world is at its most fun when colored with pathos, like a chocolate bar ground out of bitter beans. Many could have played the role (indeed, Johnny Depp did in a later adaptation, going more fey and icy), but only Wilder was able to bring to it an energy that comes from marrying threat and reward, order and chaos. It is a performance so unusual that it could only have come from, well, pure imagination.

Here are a selection of images from LIFE’s new special issue Willy Wonka & The Chocolate Factory.

Willy Wonka

Cover image: Courtesy Everett

The cast of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory on set at Bavaria Studios, located in a suburb of Munich, Germany.

Steve Schapiro/Getty

An Oompa-Loompa entertained Peter Ostrum, who played Charlie, while Willy Wonka portrayer Gene Wilder looked on.

Steve Schapiro/Getty

The Oompa-Loompas were the life of the party on the set of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory.

Steve Schapiro/Getty

The dream team: author Roald Dahl visited with actors Gene Wilder and Peter Ostrum, who were bringing his literary creations Willy Wonka and Charlie Bucket to life.

Steve Schapiro/Getty

Gene Wilder showed his soft touch on the set of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory; to the right of Wilder is director Mel Stuart.

Steve Schapiro/Getty

Peter Ostrum and an Oompa-Loompa made the most of their down time on the set of Willy Wonka & the Chocolate Factory.

Steve Schapiro/Getty

Johnny Depp (left) took on the role of Willy Wonka in Tim Burton’s 2005 movie Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, which also featured Freddie Highmore as Charlie Bucket (center) and David Kelly as Grandpa Joe (right).

© Peter Mountain/Warner Bros., Courtesy Photofest

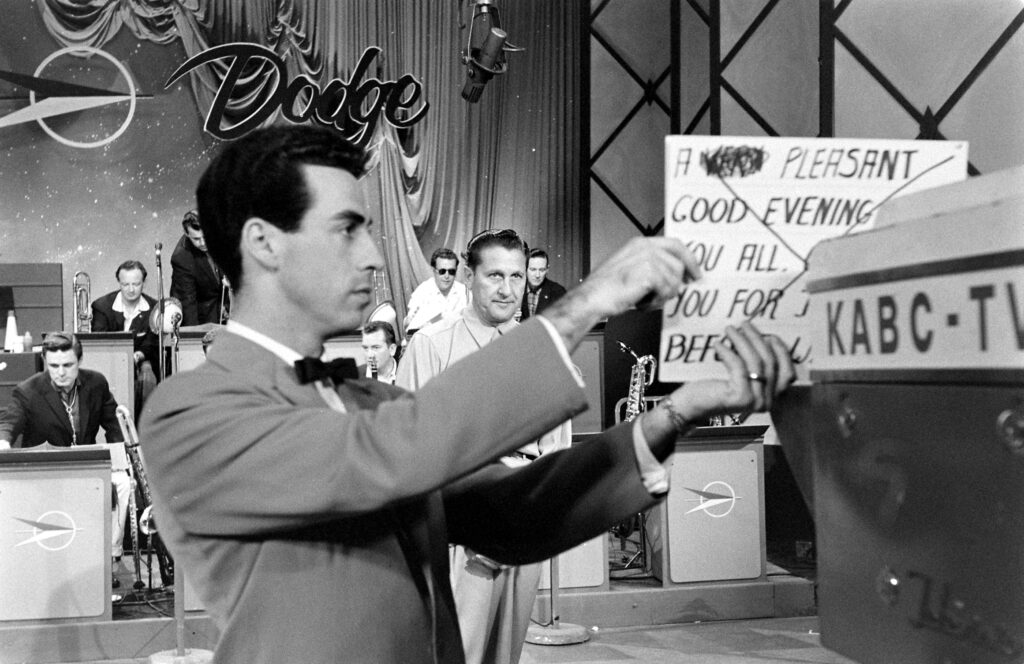

Roald Dahl, author of Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, in 1961 with wife Patricia Neal and children Theo (in tram), Olivia and Tessa.

PA Images/Getty

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory author Roald Dahl’s sensibilities showed in his choice of flash cards.

Leonard Mccombe/The LIFE Picture Collection/Shutterstock