Written By: Ben Cosgrove

Decades after its 1960 debut, Spartacus is no longer a mere movie. Instead, the strange, flawed, enthralling sword-and-sandal epic long ago entered that thorny realm where unclassifiable cinematic touchstones (Vertigo, Night of the Hunter, Brazil, et al.) reside. Directed by a 32-year-old Kubrick with only two feature films under his belt, produced by and starring mid-century superstar Kirk Douglas and featuring a galaxy of acting luminaries, the 1960 blockbuster has been exalted, imitated and parodied; honored, derided and dissected; and after all these years, it still achieves what most three-hour, big-budget historical dramas can only dream of: it’s entertaining as hell.

Here, LIFE.com presents rare and unpublished photos from the Spartacus set by LIFE’s J.R. Eyerman, who, along with writer David Zeitlin, spent time chronicling behind-the-scenes action on the massive, $12 million production.

Critics were sharply divided over Spartacus when it was first released. TIME magazine called it “a new kind of Hollywood movie: a super-spectacle with spiritual vitality and moral force.” The New York Times‘ long-time film critic, meanwhile, dismissed the movie as “heroic humbug.” Over the years, most reviewers and movie fans, alike, have come around to the view that, while the film has its problems its pacing alone drives some viewers to distraction Spartacus remains one the most successful admixtures of action-flick and high-minded drama ever attempted .

The film’s eponymous star, Kirk Douglas, had teamed with Kubrick a few years earlier, in 1957, on one of the most powerful anti-war movies ever made the lean masterpiece, Paths of Glory. Everything about Spartacus was different, more complex, bigger than that first Douglas-Kubrick pairing. (Spartacus was produced by Douglas’ own production company, Bryna Productions, in association with Universal Studios.)

Still, Kubrick’s famously fertile filmmaker’s mind adapted itself to the vast production’s scope. For example, during the filming of one enormous battle scene, Kubrick placed “numbered signs among the ‘corpses’,” LIFE reported, “so that he could holler, ‘You there, next to number 163, move over or look dead or something.’ Otherwise, he would have hollered ‘you there’ and nine guys would have hollered back ‘Who, me?’ When he was ready to shoot they took the numbers away and shot. As a technique it worked fine, but on-screen the scene proved disappointing so they shot it all over again, this time indoors at Universal’s Hollywood studio.”

Along with the photos that offer insights into Kubrick’s method, this gallery also features images that, for film buffs, resonate with far more import than the simple action depicted. For instance, one Eyerman photograph captures one of the most memorable scenes in the entire movie, involving the character of Crassus (Laurence Olivier) attempting to seduce his slave, Antonius (played by Tony Curtis), during a glacially paced bathing scene. In an often-quoted exchange, Crassus quizzes Antonius on the latter’s taste in food—specifically, how the extremely able-bodied slave feels about gastropods and mollusks.

“Do you consider the eating of oysters to be moral and the eating of snails to be immoral?” Crassus asks, and then points out that “taste is not the same as appetite, and therefore not a question of morals.” When Antonius replies that such an assertion “could be argued so, master,” Crassus shares what was surely the worst-kept secret of the ancient world: “My taste,” he says, “includes both snails . . . and oysters.”

Its sheer, occasionally kitschy entertainment value notwithstanding, Spartacus is a movie with a message that today comes across as somehow melodramatic Slavery Bad, Freedom Good and politically pointed; in fact, the anti-authoritarian rumblings that inform so much of the film are, in retrospect, utterly unsurprising. The screenplay was written by the great Dalton Trumbo, after all perhaps the most famous of the men and women blacklisted during the “Red Scare” McCarthy era that rocked Hollywood, splintered friendships and torpedoed promising careers.

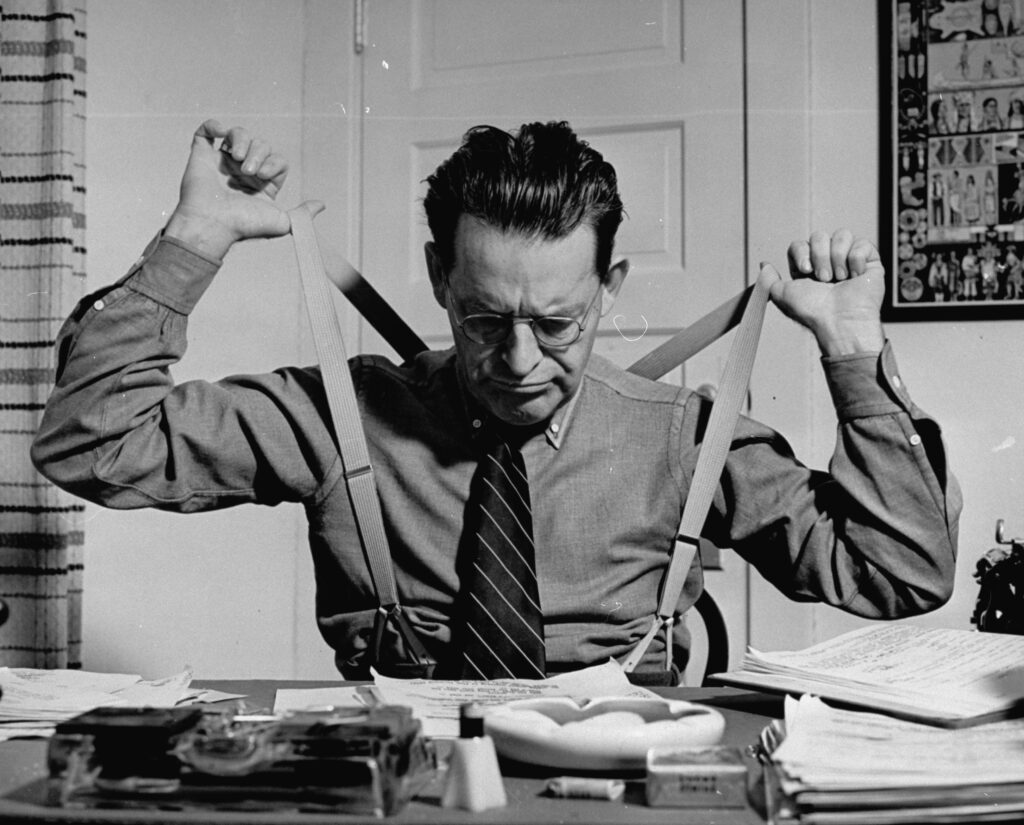

Trumbo, a member of the Communist party for five years in the 1940s, was blacklisted after refusing to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee, and spent 11 months in a federal penitentiary. Many of his later screenplays were written under pseudonyms. But Kirk Douglas insisted that Trumbo’s credit for Spartacus be made public — an act of conscience that is often cited as the beginning of the end for the blacklist era.

“Senator McCarthy was an awful man,” Douglas once said. “He blacklisted the writers who wouldn’t obey his edict. The heads of the studios were hypocrites who went along with it. Too many people were using false names. I was embarrassed. I was young enough to be impulsive, so even though I was warned against it, I used [Trumbo’s] real name on the screen.”

Long before his noble gesture came to light, however, there was still a movie to be made from Trumbo’s script, and not everyone was certain that the hugely ambitious, expensive effort would bear fruit.

“Douglas,” wrote David Zeitlin in notes to his editors at LIFE, a year before the film’s release, “I am sure will once again be old blood and guts, gnashing teeth, and Big Hero. [But] I still have considerable respect for director Stanley Kubrick. We shall see.”

All these years later, the verdict is in: as cinematic landmark and popular entertainment, Spartacus still delivers.

Laurence Olivier (right) on the set of Spartacus, 1959.

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Extras on the set of Spartacus, 1959.

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus.

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

A boom microphone slips into the frame of a photo capturing the famous “snails and oysters” scene between Laurence Olivier and Tony Curtis.

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

A view of the gladiator ring on the set of Spartacus, 1959.

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Kirk Douglas on the set of Spartacus, 1959.

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Kirk Douglas and Woody Strode on the set of Spartacus in 1959.

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

World War II vet, decathlete and football star-turned-actor Woody Strode, as the gladiator Draba.

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Kirk Douglas and athlete-turned-actor Woody Strode battle in a scene from Spartacus.

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus.

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

![Of the scene above, LIFE wrote: "Shockers abound [in the film] ... as Spartacus the slave leader deals a grisly death to cruel Marcellus, the gladiator trainer (Charles McGraw), by holding his head in a hot pot of stew until he perishes in the greasy stuff." Stanley Kubrick's Spartacus](data:image/svg+xml,%3Csvg%20xmlns='http://www.w3.org/2000/svg'%20viewBox='0%200%200%200'%3E%3C/svg%3E)

Of the scene above, LIFE wrote: “Shockers abound [in the film] … as Spartacus the slave leader deals a grisly death to cruel Marcellus, the gladiator trainer (Charles McGraw), by holding his head in a hot pot of stew until he perishes in the greasy stuff.”

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Spartacus’ Marcellus the gladiator trainer receives his just desserts.

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Having dispatched the luckless gladiator trainer, Marcellus, confident slaves prepare to launch their inspiring, albeit doomed rebellion.

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

The Roman Senate.

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

Characters played by Laurence Olivier and Peter Ustinov—as Batiatus, the owner of a gladiator school—confer during a scene. Ustinov won an Oscar for Best Supporting Actor for his performance,

J.R. Eyerman Time & Life Pictures/Shutterstock

![Of the scene above, LIFE wrote: "Shockers abound [in the film] ... as Spartacus the slave leader deals a grisly death to cruel Marcellus, the gladiator trainer (Charles McGraw), by holding his head in a hot pot of stew until he perishes in the greasy stuff." Stanley Kubrick's Spartacus](https://static.life.com/wp-content/uploads/migrated/2012/01/ugc1132371-802x1024.jpg)