Written By: Ben Cosgrove

Far more than a mere plot device heralding George Bailey’s dark night of the soul (and his joyful return to the land of the living), softly falling snow is something of a central character in Frank Capra’s 1946 holiday classic, It’s a Wonderful Life. For this film Capra decided that the cheap “fake snow” so often used on movie sets back in the day simply would not do; he wanted something as close to the real thing as he and his prop department could get.

LIFE photographer Martha Holmes documented the use of an innovative new snow-making process employed during the making of It’s a Wonderful Life—a process that, for the first time, allowed filmmakers to produce and control remarkably realistic onscreen snowfalls, drifts, flurries and landscapes.

The look and feel of holiday movies would, quite simply, never be the same again.

Movie snow in the early decades of film-making was usually white-coated cornflakes, sometimes mixed with shaved gypsum, and they produced so much audible crunching and crackling when actors walked across it that dialog was often over-dubbed afterwards. For It’s a Wonderful Life, Frank Capra, who was trained as an engineer, and RKO studio’s special effects wizard, Russell Sherman, developed their own artificial snow, one befitting the hushed beauty of a winter night in the fictional town of Bedford Falls.

Utilizing technology made available after World War II, Sherman’s crew mixed foamite — the material used in fire extinguishers and sometimes marketed under the brand name Phomaide—with sugar and water (or, by some accounts, with soap flakes) to create a substance that could be sprayed virtually anywhere, tucking tiny Bedford Falls under a wintery blanket of white.

The foamite solution was pumped at high pressure through a wind machine to create the look of freshly fallen snow on trees, streets and in drifts against buildings. Some 6,000 gallons of this new pseudo-snow were used in the making of It’s a Wonderful Life, and the RKO Effects Department received a Technical Award from the Motion Picture Academy for the development of the new white stuff. The artificial snow even clung convincingly to clothing and created picture-perfect footprints, while generating nothing like the sound of trod-upon breakfast cereal. This enabled Capra to record the film’s sound live, lending yet another layer of authenticity to the finished movie.

Capra’s vision for an authentic film experience, meanwhile, extended beyond a formula for better manufactured snow. The set for Bedford Falls was also an engineering marvel. Constructed in two months, it was one of the longest sets ever made for an American movie. It covered four acres of the RKO ranch and included 75 stores and buildings; a tree-lined center parkway with 20 fully grown oak trees; a factory district and residential areas. Main Street was 300 yards long, or three full-length city blocks.

What many movie buffs don’t know is that George Bailey’s bleak Christmas Eve was actually shot during a series of 90-degree days in June and July in 1946 on RKO’s ranch in Encino, California. The days were so hot that Capra gave the cast and crew a day off during filming to recover from heat exhaustion. In the famous scene on the bridge, before he saves Clarence the angel from the dark, swirling waters below, a suicidal George Bailey is clearly sweating—although Jimmy Stewart’s wonderful acting convinces us that fear and dread might well be the reason for that.

Stewart once said that of all the films he made over the course of his six-decade career, It’s a Wonderful Life was his favorite. Stewart, who had recently returned from distinguished service in World War II, almost passed on the role of George; it was Lionel Barrymore—who so brilliantly played the villainous, money-mad Mr. Potter in the film—who convinced him to take the part.

Made for $3.7 million, the movie was a hugely expensive production in the mid-1940s, especially considering its initial box office run only earned $3.3 million. It also happened to be the first and only time Frank Capra produced, financed, directed and co-wrote one of his films.

The disappointing box-office numbers doomed Capra’s production company, and the director soon found himself out of favor with the changing tastes of postwar audiences. But the movie—and its director—gained newfound fame and esteem as later generations were introduced to, and fell in love with, the movie on television.

“It’s the damnedest thing I’ve ever seen,” Capra once said. “The film has a life of its own now and I can look at it like I had nothing to do with it. I’m like a parent whose kid grows up to be president. I’m proud . . . but it’s the kid who did the work. I didn’t even think of it as a Christmas story when I first ran across it. I just liked the idea.”

Finally, it’s worth pointing out that in notes taken on the set of It’s a Wonderful Life by LIFE’s Helen Robinson—for an article that never ran in the magazine—one throw-away line stands out to contemporary readers. In addition to foamite, “[the whitish mineral] dolomite and asbestos were other old standbys used to dress the set.” That’s right, folks: asbestos was used as a stand-in for snow.

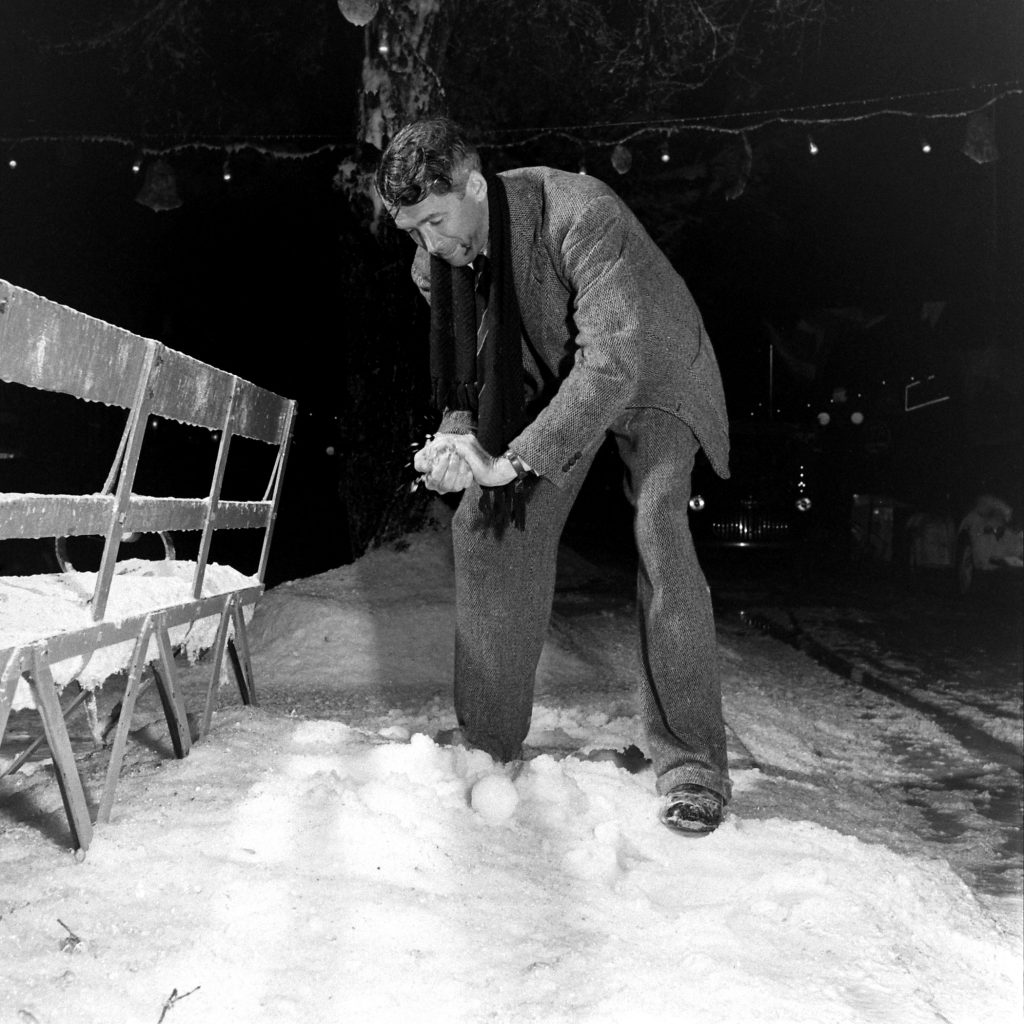

Jimmy Stewart on the set of ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’

Martha Holmes (The LIFE Picture Collection)

Jimmy Stewart on the set of ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’

Martha Holmes (The LIFE Picture Collection)

Jimmy Stewart as George Bailey in downtown Bedford Falls on the set of It’s a Wonderful Life.

Martha Holmes (The LIFE Picture Collection)

The innovative artificial snow used for ‘It’s a Wonderful Life’ earned a technical award from the Motion Picture Academy.

Martha Holmes (The LIFE Picture Collection)

The crew deployed artificial snow on the set of ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’

Martha Holmes (The LIFE Picture Collection)

On the set of ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’

Martha Holmes (The LIFE Picture Collection)

The crew made artificial snow on the set of ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’

Martha Holmes (The LIFE Picture Collection)

On the set of ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’

Martha Holmes (The LIFE Picture Collection)

Jimmy Stewart on the set of ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’ One of the characteristics of the new artificial snow was that it would stick to hair and clothing.

Martha Holmes (The LIFE Picture Collection)

Artificial snow on the set of ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’

Martha Holmes (The LIFE Picture Collection)

Director Frank Capra (right, with unidentified man) on the set of ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’

Martha Holmes (The LIFE Picture Collection)

On the set of It’s a Wonderful Life.

Martha Holmes (The LIFE Picture Collection)

Downtown Bedford Falls on the set of ‘It’s a Wonderful Life.’

Martha Holmes (The LIFE Picture Collection)